Final Exam – The best riders in training sometimes fail in racing situations. Coach Julie Young examines how top testers can prepare for the big exam, the one with a finish line – Velo News Nov/Dec 2020

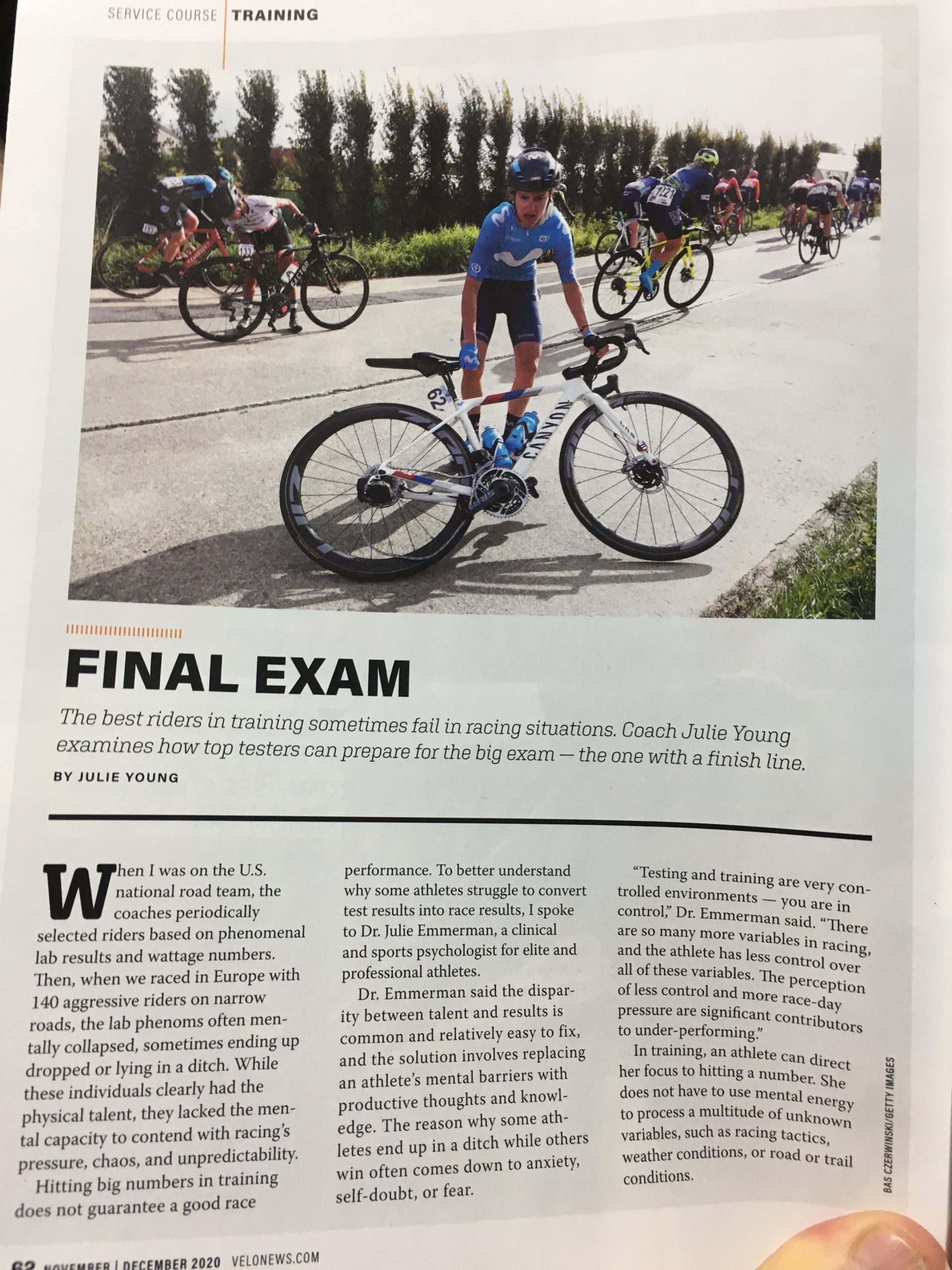

When I was on the US national cycling team, the coaches heavily weighted test results in the lab and numbers produced in training to select riders for national team trips. But when we raced European races, the likes of Molenheike, on bike path size roads with 140 sharp-elbowed determined racers, in 60 mph winds and sleeting rain, the lab phenoms sometimes mentally collapsed, upside down in a ditch or off the back and out of the race. While these individuals clearly had the physical talent, they seemed to lack the mental capacity to contend with the chaos and unpredictability of racing.

While we fixate on the more tangible factors of performance, like the physiologic and metabolic adaptations, hydration and nutrition, and sleep, we often neglect the less tangible mental side of performance. Hitting numbers in training and testing does not guarantee a good race performance.

To better understand why physically talented athletes are sometimes challenged to convert this talent into successful performance, I spoke with Dr. Emmerman, a clinical and sport psychologist for elite and professional athletes.

Dr. Emmerman says, “This is a common issue and one that is relatively easy to work with. The goal is to improve the ability to convert talent into performance by removing mental barriers and replacing them with more productive thoughts and knowledge.”

I asked Dr. Emmerman when a client is struggling with this issue, what are the main contributing factors. She says it almost always comes down to some form of anxiety, self-doubt or fear. “Testing and training are very controlled environments – you are in control, you pick the terrain, when to start, and the weather conditions. There are so many more variables in racing, and the athlete has less control over all of these variables. The perception of less control is a significant contributor to under-performing. Additionally, there is less pressure in testing and training than in a race.”

In training, the athlete’s attention and focus can be directed on simply hitting a number. They do not have to expend energy managing the direction of their attention to contend with all of these other unpredictable and often unknown variables like – weather conditions, technical roads and trails, other people attacking at will, or equipment issues.

In addition to contending with these unpredictable variables in a race situation, Dr. Emmerman points out that the athlete becomes mentally consumed with the social environment and how others judge them. To top it all off, she says, “The narrative athletes are feeding themselves can be the real kicker, like ‘this person is always stronger than me on climbs,’ ‘I never race well in spring.’ “Always” and “never” are rarely 100% true. Looking at the “mental junk food” one is consuming is important.

So, what do you do if you find yourself challenged by this issue? Dr. Emmerman says, “The first step is to ask yourself what is holding you back? Why are you anxious, fearful or feeling self-doubt? Most people have had private conversations with themselves and know these answers.”

Once the client identifies the sources of fear, Dr. Emmerman helps the athlete identify and dissect the feelings associated with those fears. Ultimately, she wants to help the athlete understand how it might feel to experience situations perpetuating the fear, differently. She says, “Gradually, step by step, I want to help the athlete get to where they want to go, versus focusing on where they fear they may go.”

Dr. Emmerman also helps the client investigate the narratives he/she is telling himself/herself that reinforce and perpetuate the anxiety and reframe those stories. She says, “We can undo these fears and use them as opportunities. We start by rewriting the narratives the athlete is telling himself/herself. We also identify the athlete’s successful performances and investigate the circumstances around those performances to make distinctions from the perceived failed performances.”

I also asked Dr. Emmerman if athletes can better use training to reduce performance anxiety and gain confidence. Training sessions are the opportunity to practice and reinforce self-talk and the revised narrative. Mental conditioning, just like physical conditioning takes training. Dr. Emmerman says, “The more athletes hone into the details during training, the better prepared they will be.” It’s valuable to use unexpected issues that arise in training to create a mindset that defaults to immediately working on solutions, versus fixating on the problem and spiraling down in frustration.

Another way to alleviate the sense of pressure and improve performance is to flip how we perceive the competition. Dr. Emmerman pointed out that our culture trains us to view competition as a venue to kill or annihilate, this means that you are either annihilating or getting annihilated. In either case, this triggers the sympathetic nervous system and fight or flight response. But she says, “In Latin, to compete means to strive for a common goal, together.” Changing how you perceive competition and valuing the opportunities it provides versus fearing it, flips how you emotionally respond to it. Dr. Emmerman says, “We need each other, to get the best out of ourselves.” Our fellow competitors, help us raise our game, be better in every aspect of performance to ride faster and stronger, and technically and tactically better.

One of the most valuable contributors to successful performance is a love of the process and competition. Dr. Emmerman says, “People who are going to succeed with sustainability are those who love the competition and the experience. They feel alive during it and don’t dread it. Getting to a place where you look forward to these opportunities is a game changer.”